The Author Wants You to Know...

Name: Dwiveck Custodio

Born & raised: Puerto Rico

Instagram: @sakurachaser @foodjourneychronicles

Dwiveck takes every opportunity to travel, cook, hear people’s stories, and read. These pastimes, along with her frequently revisited memories of her childhood, have inspired many hours of reflection on identity, connection, belonging, and home.

She loves using patterns and writing simply (but hopefully evocatively) to untangle the complex. With her words, she hopes to help people feel seen, present, inspired or to simply feel, like so many others’ words have done for her.

It’s funny how our experiences seem so disconnected from one another as we’re living them...

..Until the people they’re tied to are no longer around. Until we become obsessed with the video reel of memories and their constant replay gives them context, meaning, impact.

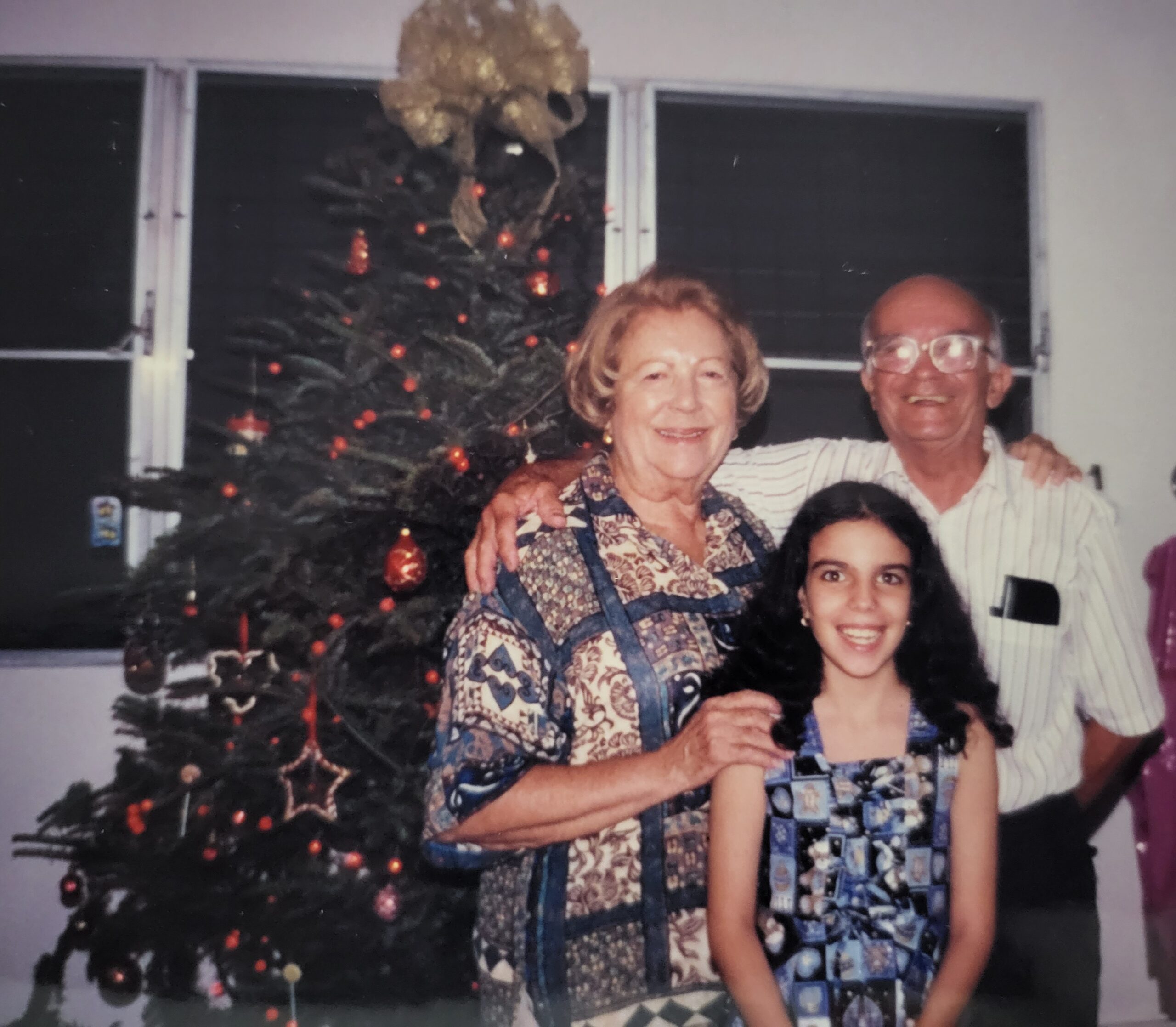

For the majority of my childhood, my parents and I lived in the first story of a two-story house and my maternal grandparents lived right above us. Both my parents and my maternal grandparents showered me with love every day. Maybe it was the world’s way of trying to balance out the fact that I sadly never met my dad’s parents. In any case, I count myself lucky. And my appreciation continues to grow the more I reflect on how these relationships shaped my life and what they taught me.

The second story of my childhood home contained the sink where Abuela (Grandma) used to bathe me when I was a baby, the hammock where Abuelo (Grandpa) and I would swing together to the tropical rhythm of a balmy breeze, the tiny tiled bathroom that smelled of peach Suave shampoo, and the porch where the largest and most magical family gatherings I have ever known took place every Christmas.

That top floor is where, years before my teachers brought up accent marks for Spanish words, Abuela taught me all of their relevant rules. It’s also where Abuelo modeled for me how to use the typewriter with which he made pharmaceutical labels. But most importantly, it is where they both planted in me the seeds of much larger, universal lessons.

That top floor is a place where so many lessons of human connection began to germinate in me, though at the time, of course, I was unaware.

Regularly on weekends—because my grandparents asked me to, or because my parents were out, or merely because I wanted to—I slept upstairs, where I received an additional dose of indulgence. After Abuelo went to his small, dark room in the back, Abuela and I stayed in the master bedroom. Abuela always started snoring long before I was able to drift off, and I loved lying in bed staring up at those burnt umber- and cocoa-colored ceiling boards, feeling at ease and alive thanks to the enchantment with which Abuela laced everything.

Sometimes we would ‘ooh’ and ‘ahh’ over figure skating competitions on TV. I dreamed of being Sasha Cohen even though I lived on a tropical island and have the world’s most unstable knees and ankles. When I was in 10th grade and an ice rink opened up, I was one of the first people to try it out. The person I most loved sharing my experience with, even though she was not present at the rink, was Abuela.

Other nights, Abuela would mesmerize me with her monkeys.

She owned a large array of stuffed monkeys of different species, sizes, and colors. I never thought to ask where she found them or why she started collecting them. But we’d lay in bed, her spray-hardened platinum bob next to my long, frizzy black curls, and she would make up tales about the monkeys for me. My mind would fill with visions of what the monkeys did and talked about under the cover of darkness while we humans slept.

I don’t remember the monkeys well anymore—except a tiny one, Titi, who lives on in my memory because there’s a professional photo of Abuelo, Abuela, me, and the monkey, who wore a rainbow bead necklace I’d strung together for her. I don’t remember the stories, either. But I remember the wonder. And I remember feeling that I knew these monkeys, I remember loving these monkeys.

When Abuela got Alzheimer's, in a wave of rashness, she got rid of all her monkeys. And I was heartbroken—for her, for our memories, and for the monkeys. I felt compassion for the monkeys—which sounds odd, I know, but I have always sensed that inanimate objects have feelings, and it started with these stories. I grew familiar with these monkeys’ thoughts, their likes and dislikes, what made them laugh, how they interacted with one another. Isn’t that what bridges gaps, forges connection and empathy? It did for me. And if these monkeys felt things, then so did other inanimate objects, and so did, of course, all living things.

Abuela’s narrative sessions gave me a love of storytelling, of putting one carefully chosen word after another to entertain, to help someone—sometimes myself—escape, and above all, to build connection and empathy.

And when all of the monkeys had left my life, when Abuela passed shortly after that ice rink opened and we could no longer bond over terrifyingly beautiful leaps or the sound of blades slicing through the ice in tune with the music, the legacy Abuela and her monkeys left me was this: A love for words. A love for imagination. A love for creating and immersing myself in new worlds. A love for stories and their power to humanize others and bring us together.

•

Since both my parents worked full-time, Abuelo used to pick me up from school and take me home every day. A man of great laughter, but few words, Abuelo showed me his love by teaching me riddles and tricks he played on people, primarily when cheating at dominoes. Years later, when I wanted to show him my love, but was unsure what to talk with him about, I would chant “agua pasa por mi casa, cate de mi corazón” (a Spanish riddle that does not translate) or “el que nada no se ahoga” (he who swims doesn’t drown) in a desperate attempt to show him that the funny words he had offered me as a child mattered to me, and lived on in me.

It’s a tragedy that during those few weeks a year we spent together after I moved out of Puerto Rico, my mind would always go blank, unable to recall the many questions I had about his life.

Now I am left with a vacuum where many of his stories should be. Neither the silly repetitions, nor the games I played with him to keep him busy and give us something to do together, will ever make up for the meaningful conversations, the passing down of history, the advice seeking-and-giving that I wish I had initiated. But they were not nothing. These interactions made him laugh, and he’d often grab my hand and jiggle it in joy and affection when I related to him in these ways.

Abuelo was also always the one to make dinner—funche de bacalao, or arroz con pollo, or ropa vieja (sweet, creamy polenta with salted cod, or chicken with rice, or shredded beef & vegetables that resemble a heap of colorful rags aka old clothes). To him, giving food was an act of love. Many times when I visited Puerto Rico from college, he would ask which night he could make me his arroz con pollo y gandules de puerco (a Spanish joke that literally translates as - rice with chicken and pork peas), a funny name he gave one of my favorite childhood dishes. On those same visits, he would ask me to go to the supermarket with him so I could pick out anything I wanted. I remember not knowing what to do on those runs. I didn’t want him to spend his money on me and I definitely didn’t want him to think I spent time with him just so he would treat me. But I also felt his frustration when I turned down his offers of an ice cream bar or a carton of juice; these were his ways of connecting with me.

After dinner when I was still a child, both of my grandparents would try to show me their love with a Flan es Cedo from their fridge, and I would usually let them. I’d eagerly unwrap my little gift, tearing the face of the flan-loving child painted on the filmy lid to reveal the red plastic basket with its little aluminium cup that embraced my caramel-drenched vanilla custard.

It was flan that I used the most to connect with Abuelo in his last years of life, when he seemed so lonely and I wasn’t sure what to talk with him about when I flew home. At this point, he’d gotten so weak that we couldn’t maintain our January 5th tradition of picking up grass from his farm for the Tres Reyes Magos’ camels (Three Kings’ Day) - a tradition we continued for decades after I found out no camels or men would be trampling through my house leaving presents. He’d started playing his favorite card games without any energy, essentially suffering through the games just to have a reason for us to be together.

During these years, eating most of his favorite foods caused him to choke. But one of the few things he still ate easily and he started loving more and more was flan. So I spoiled him. When I came to Puerto Rico to visit, I made vanilla flan for him every chance I got. And when I was too busy and we were running out of flan because he could eat an entire one in a day (if allowed to do as he wished), I’d stop at Pueblo to buy coconut flan, which I know he secretly loved more than my flan.

For his last Fathers’ Day, I sent him a dish with the words “Flan de Abuelo” and my recipe engraved in it so others could make the flan for him when I was not around.

Two months later, Abuelo stopped breathing. I got to say goodbye in person, which I will forever be grateful for, but filled with regrets. I’ve used these to grow, do better by my loved ones who are still alive, and intentionally build more and deeper connections. But when I feel like I’m spiralling down a labyrinth of regret, I hold on to the flan. He knew he brought me joy with flan, and I know I brought him joy with flan, too.

We all connect in different ways. And the little things we do when we feel useless, when we don’t know what to give? These are the stars in the darkness.

The twinkling stars, which seem so tiny from our places down here on Earth, offer us a significant amount of light. The stars are always there and, on any given night, billions of people are comforted by them. We can, we should, aim for more and bigger ways to give love. But we should not consider any effort too small to make. Some of our efforts may be small, but they are never insignificant.

•

It is in these years of reflection since my last grandparent passed that I have realized how much Abuelo and Abuela live on in me. My moments with my grandparents have given me the tools to connect with the world around me: the understanding that hearing others’ stories and sharing our own can emphasize our shared experiences and make our differences a way to enrich one another's lives. The awareness that the seemingly small details of our lives bring us together.

We all come across challenges that distance us. But with this legacy, I shift my focus. With the lessons I lived, I slowly, painstakingly, find commonalities, show people that I hear them, and deepen my empathy.

With intention, I do the work. And with practice… it does not get perfect. If perfection existed, this story would not. With practice, it does not even necessarily get easier. Each person, each connection, requires a novel approach. But with practice, and a little hindsight, I become more aware that, if I truly want to, I can connect. If we want to, we can connect.

If you enjoyed this article, why not read...

Your online magazine showcasing a collection of personal stories intended to empower, inspire & celebrate. If you've enjoyed reading...

Celebration of Self Magazine is property of WAGMAG LTD 2023